Andrei Tolstoy

Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov (1916-1995) belongs to the number of those Soviet artists who, to the full extent, personally experienced and went through all the rises and falls, potholes and gullies of an artistic process in our country, which almost always experienced pressure from the Soviet cultural powers. A professional craft which he, with a glad readiness, yearned to acquire through the lessons and teachings of such luminaries as Osmerkin, Falk and other renowned artists that had matured in the 1910s-1920s, frequently brought him to an unbreakable wall of ideology and hypocritically formed ideas of a “fight again formalism”, in actual fact it being a fight against any little bit of professional spirit and elements of mastery in the fine arts.

In the end, out of this context, which broke individuals’ fates, arose Tikhomirov’s art, full of a particular fracture and drama. And it was therefore forcedly made to be two-faced. The first face was sincere and tragic in those creations meant for himself and his narrow circle of spiritually close people; it was born out of deep searches and addressed not so much his contemporaries as his kin. The second was pompously triumphant, taking up the artist’s time as he needed to support his family and continue with his true artistic destiny.

A split in a creative individual is a big challenge, and not many are able to not only survive for a long period of time, but also reach such significant heights, in such a borderline situation. If we were to look closely at what Tikhomirov created “for himself” and what he created “by order”, a deep internal kinship of these two aspects of his art can be found. After all, an immanent integrity and organic honesty were in the highest extreme inherent in this incredibly creative individual. Yet, being in actual fact a true nonconformist, Tikhomirov was far removed from an involvement with any groups and artists’ unions.

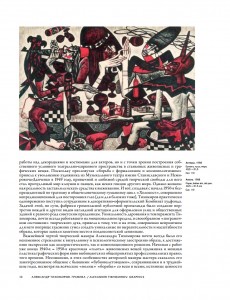

For Tikhomirov, the theatre could and did become one of the havens on the path to preserving self and his artistic values under the conditions of constant censorship. And not only in working on decorations and costumes for the actors, but also from the point of view of building a personal conditional theatre-circus space on the easel painting and graphic work. Due to the fact that the infamous “fight against formalism and cosmopolitism” led to the dismissal of the artist from the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theatre in 1949, the peculiar world of clowns and buffoons, as some messengers from another world, became his familiar and beloved sphere of creative freedom. Yet the realities of life forced him to find ways of survival. And so, from the beginning of the 1950s, creating an unprecedented “Holocaust” series, imbued with tragic and humanistic images, not at all meant for outsiders’ eyes (and for close ones’ too), Tikhomirov, almost at the same time, became a staff member at the decorative-design Art Fund Department. The task of this, in truth, vociferous public propaganda factory was to create portraits of leaders and other types of visual propaganda for the decoration of streets and public buildings for different types of Soviet festivities. The unique talent and temperament of Tikhomirov, who almost always worked on an emotional brink, in his distinctive “borderline situation” of creative spirit, brought him to the fact that even with a task that was completely disagreeable for him, the artist was able to create forms

unique in their expressiveness and size – forms that took up a noticeable place in the post-Soviet Leniniana.

The most important trait in Alexander Tikhomirov’s creative manner was almost always his unwavering yearning for a visual and psychological sharpening of the image, for the achievement of colouristic as well as compositional expression. Starting from works from the end of the 1940s and 1950s, the colourful “flesh” of the artist’s painted works and the powerful plasticity of graphical forms clearly stand out from the conventional professional rules of the time. Undoubtedly, the artist’s interested discourse with past “Jack of Diamonds” artists, that, despite all sorts of “waves” of “fights” with everything and everyone, had retained during the hardest of years the true values of carefully and strictly constructed forms and colour, showed impact on the particularities of the artist’s original manner. But even earlier, in those works done in Crimea at the turn of the 1940s and 1950s, bright colour accents and patches awaken a remembrance of famous predecessors to Tikhomirov, those who had given particular significance to the symbolism of texture – from Van Gogh to Ensor; of fauvists and other masters of art that valued an open, rich, light and colourful palette, of which there were plenty in Russia and outside of it in the 20th century. Actually, consciously or perhaps even subconsciously, the gleaned impulses of expressive shaping and forced colouristic decisions, not even mentioning the rather frequently occurring themes of an outcast, loneliness, misery, violence, joyless celebrations and mindless fun in his works, are present in Tikhomirov’s works in almost all the periods of his artistry. Gladly hiding behind the mask of a jesting clown or buffoon, not fearing the wrath of the law and speaking impudent and bitter truths straight to one’s face, Alexander Tikhomirov exercised an utterly unique manner in his work, for which it is difficult to find an analogy in the Russian art school, but to which there is a parallel in the European schools.

Let us recall the acrobats and circus performers in the works of Parisian impressionists and postimpressionists, “harlequins” and “comedians” in the works of Cézanne, Picasso and Rouault. Or all kinds of strange, grotesque personages, born out of a fantasy and temperament of German expressionists from Dresden, Berlin and Munich, or surrealists not only of France and Spain, but also Mexico and even Latin America. And finally – a shade oversaturated with brightness and a massive “dough-like” brushstroke of fauvists and their successors from the times of the “School of Paris” of the 1910s-30s (Soutine, Foujita, Kisling, Kikoine, Kremegne and many others).

The art of the first third and even the first half of the 20th century, walking unfathomed paths, sought to create minimally comfortable conditions of perception of the works of art for the viewer. This was done not for its own sake, but in order to take the viewer away from the dominating passive-contemplative world perception, characteristic of the beginning of the 20th century; to awaken an understanding of the disharmony of the surrounding life; to attract attention for injustice, suffering and challenges of close ones, and, as a final result, to see a way out and start to move towards truth and reason. This perhaps somewhat utopian and idealistic program, especially in our contemporary views, in the end, laid out the foundations of the majority of expressionistic and avant-garde life-forming artistic trends of the first half and of the middle of the 20th century, which, in their best and brightest examples persistently tried over and over again to grope at the true algorithm for the salvation of mankind through art – to find genuine harmony and beauty in the surrounding world.

Such analogies and comparisons give us only a general understanding and not at all the full perception of the context in which, perhaps unconsciously, the creative interests of Alexander Tikhomirov developed and evolved. It is possible to quite rightly argue that he turned out to be the natural continuant of many artistic directions and trends – primarily, of European art of the first half of the 20th century. And, in the first instance, because he possessed not only a bright and original artistic talent, but also because he was engrossed into universal eternal problems that worry serious artists no matter the geographical location or mother tongue. This stoical faithfulness to a once intended goal helped Tikhomirov in the situation, when his favourite teachers and he himself were “cleared out” of the university and theatre, and when he, overcoming his inner resistance, was forced to carry out official orders at the Art Fund Department.

Naturally, his favourite characters remained the most important for Alexander Tikhomirov; characters that, obeying the fantasy and will of their creator, played out imagined scenes from nonexistent plays and parables on the canvas, and built the most complex of allusions on archetypical biblical themes. Here it is possible to see different allegorical plots (“A White Dream”, 1983, “Wellspring”, 1992. and others) and the exiled from Heaven Adam, and the Fallen Angel, and the biblical Blind Men, and the Prodigal Son, and Mary Magdalene, and the Last Supper and many, many others. But usually these themes or even hints towards them were solved by the artist with the help of clown-balagan personages that first acted in some mysterious and complex, multi-figural compositions, and then simply succumbed to sleep, melancholy and spleen. Most of the personages are not at all joyful, and even if they make noise, sing, play music, it is most likely that they do this not from unrestricted joy, but from some sort of internal and reckless desperation.

The artist operates compositional techniques and position decisions for separate figures to which it is possible to find parallels both in antique vase decorations and sculpture reliefs of Egyptian tombs, as well as monumental ensembles of the Art Deco era. In this sense, the “circus-theatre” and parable personages, the scenes and themes of Tikhomirov’s canvases, present a kind of anthology of expressive and grotesque techniques, based on the complex literature program of thematic twists that retain and rethink almost all the main stages of a visual culture formation, but doing this, of course, with the advantageous reliance on the discoveries and achievements of the 20th century. It can be said that the artistry of Tikhomirov is a kind of multi-style model that synthesises and summarises a tremendous visual experience of a Eurocentric visual civilisation.

If we were to attentively and from the foot of the second decade of the 21st century look into what emerged from under the hands of Tikhomirov during the “department” years, then in these, upon first glance, stiffened things, removing all sorts of individual perceptions and neutralising any original styles, it is possible to find an absolutely innovative hand and a complete clash with the established socialist realism canons. The famous gigantic painted panneau on the facade of the multi-storey Ministry of Foreign Affairs building with the full-bodied figure of Lenin or the profile of the same persona on the facade of the Lenin State Library show a heroic and monumental image of the leader. There he appears either as a sort of Superman, or (which is probably more accurate) a great robot, a Golem of sorts, unstoppable and merciless, devoid of even a hint of some kind of human quality or feeling. Removing himself from the main, for him, artistic interests and doings with reluctance, in “ordered” works Tikhomirov revealed the totalitarian nature of Leninism and gave the official image of the leader an antihuman quality, which, in fact, remained unperceivable both for Renato Guttuzo, who appreciated

with great enthusiasm the gigantic figure on the facade of the multi-storey building, and all the more so for the Secretary General of the Moscow Central Party Committee, Grishin, who was accompanying him, as well as for other imperious “judges”.

There is one theme in Tikhomirov’s heritage, which, for a long time, was unknown even to those close to him – the theme of the frightening and ruthless Holocaust, which grows into the theme of merciless extermination of one people by another people. And although the works from the series, created during various years (the advantage is in the graphics), carry repeating titles, “Widows”, “A Cry”, “Babi Yar” from canvas to canvas, linking the themes with the tragic events from the time of the First and Second World Wars, these works – confessional, personal – have a much larger universal meaning. They are about the suppression of dignity and restriction of the freedom of individuals and entire peoples, which evokes a confident and unequivocal protest from the marvelous master. It is not by chance that Tikhomirov’s favourite personages – clowns, actors, extras – are often presented in frigid poses, with their hands twisted in a crossed-over fashion around the body, in a sort of stupor. This frigidness is the prologue to a future release, as it shows one or another character – for now only a future, potential one – in a state of inner concentration, with particular focus. Recreating and multiplying these personages in his mature and later works, developing the theme of an outcast and heroic loner rejected by the maddened crowd, Alexander Tikhomirov juxtaposed to any suppression from the “machine” – embodied either in the images of robot-like totalitarian leaders, or in a faceless mass of Nazi executioners and chastisers, or tyrants and despots that populate parable stories – the tragic decisiveness and unwavering inner freedom of any individual who unwaveringly preserves his spiritual dignity, especially an individual that has dedicated himself to artistry, and one capable of revealing the tragic essence of being. The prominent Russian artist Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov was the shining example and image of such unbending creative personality.