Leonid Katsis

«IN MEMORY OF THE INNOCENT VICTIMS», 2013

The relationship between the artist and the epoch has never been of a linear nature. It would be incredibly simple if everything that God had given to a human being was implemented progressively and naturally. However, this is practically impossible to happen due to the fact that at some point humans have been exiled from Heaven. And after this, the mankind itself seeks reasons for its troubles and misfortunes in the depths of the biblical history. The XX century has, among others, posed a new question – the question about the extermination of the Jewish race in the hearth of the Second World War, having made their deaths a subject of topical discussions of the Jews themselves as well as the rest of the world.

Not so long time ago, speaking of Alexander Tikhomirov, we would have to focus our discussion on his biography, on the main stages of his artistry, and on the destiny of his heritage. However, after several exhibitions in the Russian Museum in St. petersburg, in the Museum of Eastern Art in Moscow, as well as others, there is simply no need for that.

The time has come to evaluate his views on the impactful tragedies that found their way among the events of the XX century, symbolised by the words: “Auschwitz”, “Babi Yar”, “Holocaust”.

Alexander Tikhomirov mostly worked during the period of time when, out of this triad, the most important were the first two symbolic terms. It is therefore not surprising that in a separate folder with graphic work, collected by the artist himself, we see these two themes.

Tikhomirov is an artist with a philosophical state of mind. Tikhomirov is a Russian artist. And his views on the tragedies of the XX century differ fundamentally from those of numerous Jewish artists.

Tikhomirov did not dedicate that many of his works to “Auschwitz”. However, it is exactly “Auschwitz” that brings the theme of the Catastrophe up to a global level, allowing it to break past the boundary of the traditional – for Soviet times – blurry definition, where Jews, Russians and Gypsies, both civilian and military, were characterised as “Soviet people” and abstract victims of the Germany Fascist invaders.

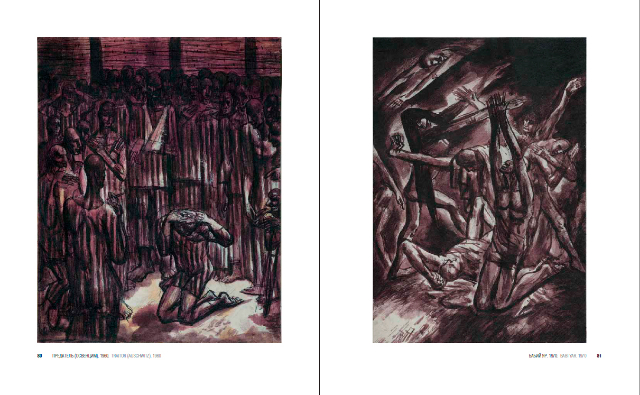

However, before actually starting to work on the paintings, associated with “Babi Yar”, Tikhomirov reflected on the tragedy of war and of the whole XX century in the context of the most prominent symbols of the European culture.

It’s enough to take a glance at the position of the body and clothing of a man in a striped robe on the painting “Traitor (Auschwitz)” (1960), to recognise the posture of a thief crucified together with Christ, known by its classic interpretations, including the ones by Tikhomirov’s favourite Nikolai Ge. It leaves an impression that Tikhomirov placed one of the Calvary culprits on their knees. And it comes across as such because, unlike those standing in a circle of the doomed, only the “Traitor” was left standing in nothing but a shirt. His bare legs, pressed towards the ground, graphically remind us of the position of the crucified’s legs in the painting of the XIX century artist.

Evidently, the circle of the doomed has never condemned the true Evangelist traitor, Judas. The decision to hang himself on the aspen tree was a result of his own moral sufferings.

Such a fable duality must always be kept in mind when looking at the paintings and graphical interpretations of Tikhomirov. Most of them are an attempt to portray the experience of the XX century artist in classical terms, however, combined with modern experiences as well. It is to be noted that naturally, the artist’s feelings are expressed with consideration to the development of the artistic language of the following centuries, and sometimes even decades, if we are speaking about the XX century, that is.

The difficult thematic and artistic structure of the “Traitor” is typical for Tikhomirov. This affects not only visual images of death, suffering and memory.

In order to understand this it is vital to look at the works on “Babi Yar” (1955, paper, graphite) and “A Memory (Babi Yar)”, 1955.

At first glance, these come across as somewhat peculiar works of art, where a group of monumentally modelled figures prepared for the people’s death is offset by a singular figure of the comedian on one of the works, and by the same figure, this time from the back, beside a standing figure of a grieving woman on the other.

How does theatre come into it all? This question arises only in the case of you not knowing that the portrayal of the World Theatre is perhaps the most important for Tikhomirov in the period of 1970–1990s. Moreover, if recalling the attentiveness of the artist towards interpretations of “King Lear” in the film of Grigory Kozintsev, and the books, then the small stooping figure with the broken gestures of an actor suddenly reminds one of the cry of another “Lear” – Solomon Mikhoels – over the body of Cordelia.

The second drawing, where a suffering balding elder is being soothed by a woman in black, may therefore come as a shock. But let us remember what sort of year 1955 was exactly. It is the year when families of victims of the process of the Jewish-Antifascist Committee returned from exile. The year in which widows returned to find out the

destiny of their husbands. But this is also the year, when, for instance, the widow of Peretz Markish – Esther Markish – searched for a person who could translate her husband’s poetry: “The Inextinguishable Light” to commemorate Mikhoels. In this poetry, which was even discussed during the poet’s trial, there is a symbolic image: Mikhoels fell onto Minsk’s snow banks in memory of those that fell during the war, but they will rise together.

It does not matter whether the artist knew this poem or not. Although, he could well have known it. History of the creation of this poem is complicated. Officially, and in Yiddish, as well as in Russian, this poetry emerged only in 1957, however this by no means suggests that it wasn’t known… The job of translating it was offered to B. Pasternak; the translation was eventually done by Arkady Scheinberg for a book published in 1957.

For us it is important to notice here that dual structure of artistic expression of image, which is ever-present in Tikhomirov’s work.

We have grounds to believe that the figures on the two “Babi Yar” paintings are Jewish, including the naked female figure half-way submerged into the pit. Pictures of naked women before the shooting have not been a rarity in the Soviet press up to a certain moment. It is therefore possible to apprehend the complexity in the restraint of Tikhomirov’s artistic language, when a naked figure, so familiar because of the newspaper photographs, vanishes into the nothingness as a shadow. From here stems the theme of shadows in the graphics, where, on the homonymous works, groups of people move into metaphysical distance. In later works of “Babi Yar”, we can see the attempted portrayal of suffering by a man who has no relation to it. Such way of putting it should not come out as a surprise, as the theme of Holocaust has not been a central or main one for the artist. That is why in the work “Babi Yar”, 1968, beside a group of huddled people, on the left there stands a man and a woman portrayed in a position which is visibly typical to iconography. Their hands, cross-folded on the chest, suggest this with all certainty. And it could not have been otherwise. For a Russian, the Bible is not solely the Old Testament, but also the Gospel. Artistic language of the Russian Bible is iconography. However, such language was absolutely unacceptable in Soviet Russia in the 1950–1980s.

It seems that we need to once again turn to the closest historical context. The theme “Babi Yar” became symbolic after the appearance of the famous poem by Yevgeny Yevtushenko in a 1961 newspaper release. The first lines: “Over Babi Yar there is no monument…” with no doubt posed a question about the monument in that place.

However, the announced 1965 contest never came into being. In 1967, the six-day Arab-Israeli war broke out, in 1969 the author of the famous documentary book “Babi Yar”, Anatoly Kuznetsov, fled to England. Not even mentioning the fact that events of 1968 in Poland and Czechoslovakia have also been regarded in context, excluding any chances of erecting a monument in memory of the killed Jews. It must be said, though,

that banning concerned monuments to activists of the Ukranian national movement killed in Babi Yar, orthodox and non-orthodox priests and others. All this became possible only after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

And in those years it ware only the “voices of enemies” speaking of meetings in Babi Yar with involvement of the Russian writer Victor Nekrasov, and courageous Urkanian intellectuals then called “bourgeois nationalists”.

Nekrasov’s first article devoted to Babi Yar had been published in “Literaturnaya gazeta” back on 10th of October 1959. And ever since Victor Nekrasov had repeatedly referred to this topic. In 1966 Nekrasov published an article in “Decorativnoye iskusstvo” magazine (issue number 12) devoted to “New Monuments” contest. Due to the beforehand-made decision allowing the publication (typical of those times) the magazine has been published despite the big meeting which took place on 29th September 1966 on occasion of the 25th anniversary of the shootings in Babi Yar, where the Russian writer Nekrasov said that there will be a monument here, in the place of murder of the Jews, and Ukrainian literature critic Ivan Dziuba, and others spoke of the death of the Jews.

It makes sense to revert to Victor Nekrasov’s article of 1966, in order to feel the moral and political context of the time. The year of 1966 was special, – a trial of Sinyavsky and Daniel took place in February that year, marking an important milestone in the ending of the «Thaw». At the same time allied republics had been triumphantly reporting about their achievements before the celebration of the 50-year anniversary of the Soviet Union. This article was published in a journal under the pretence of the Ukrainian artists’ report on the upcoming symbolic day. The number had been sent off for publishing before the meeting in “Babi Yar”; otherwise the article of the contestant would have never been let through.

It began with the image of “the Monument project, dedicated to the 50-year Soviet rule” for the Kalinin Square in Kiev, and demonstrated a huge Lenin with three marines marching at his feet. The monument was mentioned only in the incision by the editor’s office.

Here are the first few lines of the article:

“Babi Yar

Twenty years have passed since the 29th September 1941, a day memorable to all Kiev residents, when in the deep pit, on the far side of Kiev, there sounded the first shots of machine guns. Over the twenty years, a whole new generation has grown. For them, events that took place there belong to a faraway history – the “Babi Yar” events have been washed off*. Now you will find here a vast, flat wasteland, overgrown with wild grass; homes have been built all around it, a whole new city district, and nothing remains of what could remind one of the awful tragedy that erupted here on the bed of this non-existent ravine. Neither an obelisk, nor a stone – just a wasteland. Ask the inhabitants of the new buildings, and not many could tell you what exactly had happened here at that certain time in history.

An end has now come to this unnatural oblivion. The contest for the monument in “Babi Yar” was announced over a year ago and, moreover, has already been carried out, although no conclusive decisions have yet been made. This is the topic, the contest – although rather the thoughts that it provoked – which holds interest for a discussion”.

The main protest point of Viktor Nekrasov was linked to the idea that even the contest’s programme itself, stating that the monuments in “Babi Yar” and in the prisoner of war camp in Darnitsa (both in the same programme! – L.K.) “…must express artistically the heroism and undying will of our nation in the battle for victory of the great ideas of Communism, for the honour and freedom of the Motherland, courage and fearlessness of the Soviet people (here it is, the official statement that appeared on the monument in 1976! – L.K.) before the face of death from the hands of the German executioners, should show the brutal faces of the Nazi invaders. The monument must also show the national mourning for the thousands of unnoticed heroes, who gave their lives in the year of the German-Fascist occupation. If I were to take part in this contest, and having read the conditions, I would have, in all honesty, felt myself facing a dead end”.

And this is, of course, inevitable even with a minimally honest approach in tackling the task posed by the authorities.In this very article Nekrasov himself explains his position: “Why then – if returning to the conditions of the contest – would they have placed me at a dead end? Because the monument in Babi Yar is a memorial to the tragedy of the helpless and the weak; the monument in the Warsaw ghetto is a memorial to the uprising, battle and death; in Darnitsa – for brutally shot soldiers, combatants, civilians, captured while fighting – people mostly young and strong. Babi Yar was a tragedy of the helpless, the old, those singled out by a special mark. The history of the Second World War (and in that, of all the wars) never knew such mass and time-compressed slaughtering.

I mentioned the world “tragedy” three times. And emphasised it. All done consciously. For some unknown reason we fear this word. And its meaning. And if we resolve to use it, then always in context of heroism and resistance. What if neither one nor the other existed? What if there was only barbarism, bloodshed, and death… What then?”

Nekrasov spoke in favour of creating a maximally subjective monument consisting of two stellas leaning towards each other.

But Tikhomirov, an artist, took a different approach: he dreamt not of an abstract sculpture, but of a multiple-figure group which, obviously, had no connection to the semi-official “programme”. The contest itself, it seemed, was chiefly Ukrainian rather than that of the Union. Hence, under no conditions could he, a Moscow author, participate in such a project.

The short article by Viktor Nekrasov came out in a special – and not without a Fronde – art magazine. It was not up to him to define political and artistic atmosphere in the country. A country, where the word “Jews” was not used on principle, except in the propaganda about the solution of the “Jewish Question” in the USSR.

Throughout all these years, in the Soviet Union, massive work has been carried out on the establishment of the monuments and memorials (of various quality) to heroes, events and victims of the Second World War. Lenin and Government premiums have regularly been given for these works. Openings of such constructions have been attended, as it was then called, by the “leaders of the party and the government”.

At the end of the 1960s – beginning of the 1970s – new and remarkable monuments began to emerge, for example in the Salaspiels camp in Latvia. It is not by accident that we have recalled here this particular monument. Let us bring our attention to its central figure, standing almost in the same position with its uplifted left arm and transversal right arm bent at the elbow, just like on Tikhomirov’s painting.

Although, unlike in the monument in Salaspiels bound to demonstrate unyielding courage, as it used to be in those times, the right arm of the man on Tikhomirov’s drawing is bent at the elbow and falls towards the shoulder, instead of “completing” the actual concrete quadrangle of the Soviet monument. This is very close to the view of Viktor Nekrasov, who did not accept “strength and a confident look into the bright future”, so common to the Soviet monuments, even those made professionally and of good quality.

It seems that we could attempt to explain sharp changes which took place in Tikhomirov’s graphic language as a reflection on the events of 1965-1968 (from the announcement of the contest for the monument in Babi Yar to the Prague Spring). Monumental motifs started breaking into his flat, strong, compositionally graphic drawings. Monumental in the most literal sense of the word.

From this moment, the artist begins his difficult and secret from sight work on the monument to the victims of Babi Yar.

As we can imagine, this change in the graphical manner of Tikhomirov includes another far-from-Soviet context. The commemoration of the Second World War went on not only in the USSR. The closest context to Tikhomirov’s portrayals is perhaps the monument of Ossip Zadkine called “The Ruined City [Rotterdam]”, which has many times been depicted, even during the Soviet period. It is also absolutely clear that such drawings in one way or another reproduce shapes and motifs of the sculptures and drawings of Rodin, without which it would have been impossible to comprehend memorials of the XX century, rising to the ideas of the Parisian School.

Another stylistic context for Tikhomirov’s artwork appears to be the illustrations of Ernst Neizvestny to the novel of F. Dostoevsky with the symbolic, in our case, title

“Crime and Punishment”, which were published in the year 1970 in the series called “Literary Monuments”.

In contrast to Ernst Neizvestny, a sculptor, who, in one way or another, could express his graphic images through stone, bronze, etc., with Tikhomirov these images did not live so much in the sculpture form but became a part of the metaphorical line of theatrical, biblical, generally philosophical arrangements, giving art weight, heaviness, and sudden graphicality.

Many years later Neizvestny put up a monument to those who died in Stalin’s camps in Vorkuta, where both a huge mask, and a grieving figure, although in completely different space and architectural proportions, evoke memories of Tikhomirov’s suffering masks in “Compositions”, 1955, or in the painting “Babi Yar”, 1965. But in one of the projects for a monument in Babi Yar, presented in the form of illustrations to the article of V. Nekrasov, we suddenly see a similar mask-face, jutting out from the flat stone figure. It is interesting that one of the variants of the monument for the victims of Stalin’s repressions done by Neizvestny, consists of a whole pile of masks expressing suffering.

This is how artistic and symbolic language of the memory, which was not allowed to realize itself in the Soviet times, slowly rebuilds itself; the language of those monument sketches, which should not have even been shown through contest models, that now remain only in folders.

Series of graphics “Babi Yar” is a unique phenomenon in the history of apprehension of Babi Yar tragedy. And its uniqueness comes through at the forefront of works by Jewish artists, who have worked on this same theme.

Among those close to Tikhomirov there was an artist, Yefim Simkin, who also dedicated many works to Babi Yar. However, for him, for one who was brought up in a Kiev orphanage such a theme was hardly escapable. For Tikhomoriv, it was an addition to the general line of evaluation on problems concerning crime and punishment, feelings of guilt and empathy, misfortune of others and its inclusion into one’s own spiritual experience. It could have been the experience of Greek tragedy and of biblical Christianity, as well as the experience of his predecessors in Russian and world art.

However, his personal spiritual experience inevitably implied experience of the Soviet art. It makes sense to compare the painting “Babi Yar”, 1968 , with the famous piece of E. Frih-Har “Friend’s Funeral” (1926), exhibited in The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

A group of figures portrayed in “Babi Yar. Composition 1” is composed of the same thick masses and figures. However, while Frih-Har’s heavy wooden figures carry a

coffin with their friend’s body on their shoulders, Tikhomirov’s composition is resolved in an essentially different way.

At the bottom of the work we see a parallelepiped. Following the well-known drawing rules his massive black frame takes an observer far into the depths of space. And here, on a relatively fragile foundation we see a group of heavy, grieving figures, looking into that very depth and ready to fall into it.

The famous heavy coffin, carried by the heroes of Frih-Har, is portrayed here as a light veil of mourning, which covers the grieving figures. And this also is not so much a replica of a well-known group but a horrific reality – no victim of Babi Yar was entitled to a coffin.

Tikhomirov’s attempt to always reflect on his life experience came through even in the folders of works associated with Babi Yar, where drawings were found that could well have related to the tragic fates of Armenians in Baku in the years when the artist lived there.

As a matter of fact, the painting “Widows”, 1963, does not have any marking related to “Babi Yar”. Neither does it possess sculpturality that characterises works of a slightly later period, which we have associated with an idea of a monument to the victims of Babi Yar.

Let us not forget that uneasy issues of national relationships in the USSR included not only silencing of anything related to the tragedy of Babi Yar, but also events leading to the then unresolved Armenian-Azerbaijiani conflict. The tragic events in Sumgait and Baku occured in the last decade of Tikhomirov’s life.

In some cases, as with the painting “Babi Yar”, 1961, where human figures fall into the abyss, we are able to see the row of ideas, which were, in our opinion, realized unsuccessfully in the official monument to the killed “Soviet people”, erected in 1976 in Babi Yar.

Furthermore, from different points of view, the crossing and entwining of arms and legs of the victims, sliding down into Yar on the monument, remind us of much more successful graphics of Tikhomirov. Either way, the comparison of a semi-official social piece with a truly artistic piece of art is always a task that is little appreciated.

Importance of presenting the cycle of “Babi Yar” to the audience shows that the sudden philosophical depth of Tikhimorov’s easel graphic works of the 1970s, easily noticed against a background of the officious Soviet monuments, was not at all incidental. His works inhaled that spiritual experience of understanding and tragedy of Babi Yar, the feeling of helplessness and evenshame, in addition to understanding the

impossibility of showing his soul-burning grief in a symbolic, open and earnest artistic way, directed at the observers.

This feeling was common for honest artists, whose active creative life happened to fall on the second and the third quarters of the XX century.

____________

* When using this strange expression Victor Nekrasov meant tragic events in Kiev, when during the construction works in the Babi Yar area the city was hit by debris flow which took lives of over 100 people. The writer used the double meaning of the expression “washed off” – authorities did not only try to erase the memory of those who died during the war, but also to silence a new tragedy related to this place. – author’s note.