Anna Matveeva,

Fontanka.ru Peterburgskaya gazeta, 2011

Exhibition of works of Alexander Tikhomirov – Soviet artist creating Lenin’s portraits for living and parable paintings for the sake of heart – has been opened at the Marble Palace.

Alexander Tikhomirov has been drawing Lenin’s portraits for almost thirty years. He painted them in the times of Stalin, Khrushchyov and Brezhnev. He also painted portraits of other party leaders, including current Secretary General of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. That was his job: from 1949 to 1976 Tikhomirov worked as an artist at the Moscow Decorative Art Concern. The Concern dealt with streamline production of posters for visual propaganda, later on posted on the streets of Moscow. That’s where Tikhomirov has set the world’s record – created the biggest Lenin’s portrait in history. On national holidays canvas 42 to 22 metres in size was displayed on the front wall of one of Stalin’s skyscrapers – building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

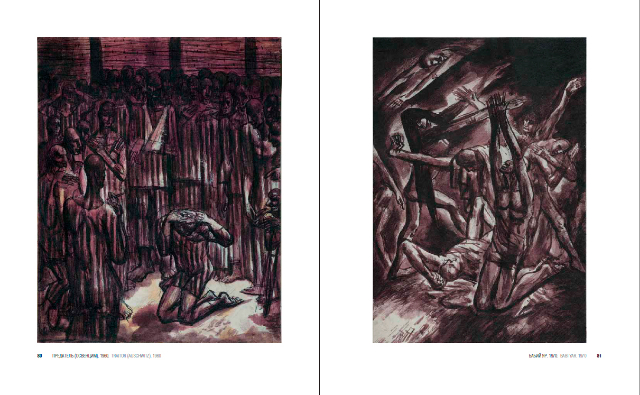

Nothing of above-mentioned is displayed at the exhibition recently open in the Russian Museum. Completely different paintings are presented in the halls of the Marble Palace. Created by Tikhomirov when he was free from Lenin, they have almost not been exhibited. He needed them for himself, for “the sake of heart”. In the evenings and during the week-ends official poster designer and decorator was taking off his mask to reveal an artist-narrator underneath. There are five dozens of canvas and drawings at the exhibition. Tikhomirov, being the student of Alexander Osmyorkin, one of the members of “Jack of Diamonds” society – has been over decades polishing his own manner of painting, however, the influence of “Jack of Diamonds” is as visible in his later works as in the ones created during his student years. By the 60s his paintings have already acquired all typical features which the artist shall remain loyal for life: solemnly obscure colors – red, purple, deep blue, black. Sharp lines, drawn with force, thick relief strokes, paint congealed in gibbous twists and nuts. And people.

People were the only object deserving Tikhomirov’s attention. To be precise, not people but characters. Each of his paintings is a parable, an action put by the artist on canvas like a play put on the stage by stage director. And it’s not accidental that vast majority of his characters are actors, motleys, buffoons, petroushkas. People wearing masks and make-up; people, whose profession is to bring joy and horror, presenting the audience with fiction filled up with truth deep inside. As he used to say himself: “Motley belongs to the society, as it’s him who tells the truth into your face”. Theatre, buffoonery, its magic dazzled Tikhomirov. The way magic tails away has also captured him: his actors, equilibrists and clowns, with their make-up on, take a sit at a scanty table, play cards and set off on a journey.

Tikhomirov’s art itself is theatric to the marrow of the bones: instead of producing the leaders’ portraits in bulks, from Monday to Friday, he’d better decorated performances and painted the sceneries. Everything in his art is too much, too expressive. If there’s a light – there should be fire, if there’s a shadow – it should be pitch-dark, if there’s a gesture – it should be done vehemently, if there’s a voice – it should evolve into scream. Looking at the picture of 1958, called “Scream”, hands instinctively reach out to cover the ears: even classical Munch does not scream so much with paint. And Tikhomirov naturally screams, with pictorial “meat” breaking loose, kilos of paint, smashed into the canvas and stiffened in a petrified whirlpool. Each painting is first of all a story and each story is a drama: “Obsessed Man”, “Outcast”, “Victim”.

Such painful psychic strain is not rare for Soviet “slightly left” art of 1960-80s. Creative intellectuals preferred to have existential talks after work. Their ambitions were not high enough to come up with their own philosophy: the philosophy was scientific, by Marx-Lenin, however, it did not prevent them from searching paramount meaning of life and having discussions about destiny and soul – later on disparagingly called “imperishable soul search” by the next, much more cynical generation, – and which became a real escape for them. Parable and metaphor used as the main expressive tools both in literature, starting from Strugatskiye brothers and up to Aitmatov; in the theatre and – in the art of Alexander Tikhomirov.

Exhibition is devoted to the 95th anniversary of the artist. Tikhomirov’s life has been a long one: born in Baku a year before revolution, he died in Moscow in 1995. He has never joined any art movements, has neither been a fighter, nor a dissident. Entire history of Soviet unofficial art with its bulldozer exhibitions and private viewings in the apartments has bypassed him. He felt more comfortable in the theatre of his own spirit. There he was the stage director, created his own actors and did not need any spectators.