Sergey Khachaturov

«Russian art» magazine, # 4, 2011

Missionary work, carried out by the artist A.D. Tikhomirov’s heritage Foundation of (1916 – 1995) nowadays brings back the name of the master, whose art to much extent allows us to perceive Russian art of the 1930-1980s not as a scary shadow of the free artistic world, but as a rightful participant of the great dialogue of arts. Alexander Tikhomirov lived in such harmony with the latest XX century art systems and methods that it’s amazing how it can be that he is not a representative of a Paris school, for instance, but a native of Baku, who later on lived in Moscow but has never been abroad.

That was a paradox of pre-revolutionary times when the artist was born that many of the capital cities of newly established state became a place to meet and socialize for many devoted and highly educated masters. And Baku was not an exception. Theatric art flourished there and Tikhomirov drank into it; there worked heirs of the great pictorial traditions of the Russian realism, such as, in particular, Repin’s student Ilya Gerasimovich Ryzhenko, who gave Alexander Dmitrievich his first art lessons. Having moved to Moscow during the Second World War (in 1944, as Tikhomirov has been released from military service due to blindness in one eye), the artist has been admitted to Moscow State Institute named after Vasily Sourikov. And again he was extremely fortunate to take classes of the highest quality. Over four years Tikhomirov had an opportunity to learn from famous representative of the Russian sezannizm, member of the «Jack of Diamonds» group Alexander Osmyorkin. And again we come across the theme of sensitivity and perceptiveness to everything that became classics of the world’s modernism: to the followers of Cezanne, and, in a broader sense – to the followers of great deeds of a new French school, fauvism and cubism. Clearly enough, in 1948 Tikhomirov, as well as his teacher Osmyorkin, has been expelled from «sourikovka» for «formalism», so much hated by official social-realistic party line.

Interestingly, since late 40s and up to 1995 – the last year in life of Alexander Dmitrievich – there were no big events which could be discussed at a high official level. With maybe one quite strange exception – two gigantic portraits of Lenin which entered the Guinness Book of Records. The portraits, over 40 to 20 meters in size and during the Soviet times were regularly used to decorate fronts of the buildings of the Lenin’s State Library and the Ministry of the Foreign Affairs on Smolenskaya square on occasion of anniversaries of revolution. During one of such holidays famous Italian communist painter Renato Gutuso was passing by main streets of the city, and praised the portraits. Lenin’s portrait displayed at the building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was awarded with the golden medal at the visual propaganda exhibition held in the Exhibition of National Economy Achievements.

Nevertheless, I’m sure that it was the second period of Tikhomirov’s art life, almost half a century long, which had the most value. During this period of time his own method, repertoire and life values and priorities take shape. Ancient books, Bible, theatric art, charged with Shakespear’s poetry, and classic music have constituted the world of the artist, so distant from both official trends and so-called unofficial culture which was blossoming in 60-90s.

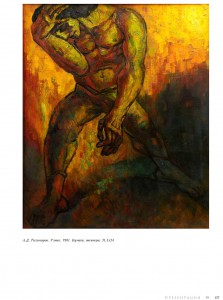

It was his creative generosity and sensitivity to the essence of art as such which did not allow him to use the language of posters, become prosecutor or herald on various sorts of rostrums. He was vigorously, with incomprehensible passion polishing discovered themes and motives to perfection, making picturesque and graphic performances where his favourite characters were mainly Pierros and Halequins, main figures of commedia dell’arte. Through their tangible, over-strained physical sufferings he talked about torturing of art in present times. Least of all would one want to associate Tikhomirov’s clowns and prisoners with critics on the lack of creative freedom in Soviet state environment. Among his contemporary companions is Fellini with his eternally tragicomic and at that admirable and lovely life pantomime, and possibly masters of neo expressionism like Georg Baselitz, associating in his works sufferings of the human flesh with throes of child-birth of the mother nature. Undoubtedly, this is a music of a century, bursting in cascades and often linked to contemporary dance and image theatres of Stravinsky and Prokofyev. Looks like it has been exciting for Tikhomirov to unfold his picturesque mysteries at such a level and with such associates.

Can we call the painter’s strategy an escapism in relation to the art life of his days? Both yes and no. Yes – because he was practically doomed to fall out of the context of events. No – because when making his choices he never strived to escape, slip away, disappear completely. It’s enough to take one more look at his giant prisoners, mighty plastic of compositions, breathing volcano of colours in many of his works, and it’ll become clear that he accepted life with its vital energy and its powerful juices. And he accepted it because he was in love with the world culture. Arts expert Vladimir Moskvinov called Tikhomirov «Soviet Michelangelo. Well, a dialogue with this Renaissance titan was important for him as well. The body as phenomenon and at the same time a prison of the soul – this is a leitmotif of Tikhomirov’s art.

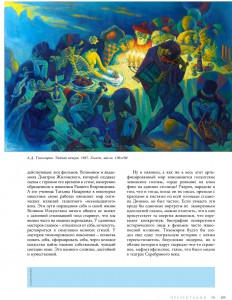

Moreover, in itself, the strategy to understand and justify the reality through art but not politics – has been an obvious and easily traceable trend in the art of Tikhomirov’s generation, those of them who were far away from the politics. In his «Ivanovo detstvo» and «Zerkalo» Andrey Tarkovsky uses albums and reproductions of masterpieces as kind of camertone of life of his films’ characters. Remember academician Dmitry Zhilinsky who created scenes with people of his time in a style, deliberately directed towards the art of Early Renaissance. And his student Tatyana Nazarenko in some of her most famous works revitalizes the world of optic illusions of gallant «eighteenth» century. These ways to acquit themselves and their lives with the Great Art have nothing to do with salon «semi-antique» stylized design which can often be seen at the fashion shows in our days. The most important for salon masters is to give up their own self, disappear, dissolve in simulation of the great styles. And for the masters of Tikhomirov’s times it was an attempt to understand and form themselves, to find their own quotation-free language through the great art. This is more difficult and takes much more dignity and courage.

And, finally, how do these enormous Lenin’s heads, proudly thriving against the red background on the buildings of the capital, fit into such an artified world? I’m sure, the paradox lies in the fact that he was honest even when he was creating them, walking across the field of Dinamo stadium. If you look at these odious portraits not through ideological prism, you could see that they contain energy of art allowing to transform specific biography of a specific person into a phenomenon of pure illusion. It seems like Tikhomirov created one more theatric story with some kind of a giant hero, undoubtedly a leader, whose image contained something scary, Mephistophelean, that something which was in fashion in the Silver Age theatres.