Milestones of life and creative work

- 1st January 1916 – born in Baku.

- 1931 – begins studies at a technical school and works at Baku’s advertising art studio.

- 1934 – enters into a second year art course at the Baku Art School.

- 1935 – is transferred to the class I. G. Ryzhenko, V. E. Makovsky’s student.1937 – participates in an exhibition at Azerbaijan’s State Museum of Art, dedicated to the 750th anniversary of the publication of Shota Rustaveli’s poem, “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin”.

- 1937 – several of A. D. Tikhomirov’s works are obtained by Azerbaijan’s State Museum of Art.

- 1938 – works in the Art Department of Azerbaijan’s Antireligious Museum.

- 1938 – enters the Union of Azerbaijani Artists.

- November 1939 – marries Nika Nikolayevna Kovalenskaya.

- From August 1941 to August 1944 – works in the Creative Production Department under Azerbaijan SSR’s Art Foundation.

- August 1942 – death of his wife Nika.

- September 1944 – enrolls into a 3rd year graphics course at the Moscow Architectural Institute (from 1948, the V. I. Surikov Moscow State Academy Art Institute).

- April 1946 – marries Natalia Anatolievna Vinogradova.

- From May 1946 to March 1948 – works as an artist at the portrait-art studio under the Pictorial Exhibition Production Department.

- August 1948 – birth of his daughter Anna.

- August 1948 – is enlisted into the art production studios of the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko theatre as an artist-painter.

- October 1948 – dismissed from the V. I. Surikov Moscow State Academy Art Institute.

- July 1949 – due to the reorganisational program, is fired from the art production studios of the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko theatre.

- From June 1949 to May 1950 – works in the art production studios of the Central Park of Rest and Culture.

- From 1950 to 1955 – studies at an artist qualification raising studio at the MDAF USSR Department of Applicable Decorative Art.

- From March 1951 to April 1976 – works at the MDAF USSR Department of Applicable Decorative Art.

- 1975 – obtains a personal studio.

- From 1976 to 1995 – retires and continues to epitomise his creative ideas. The artist’s works are acquired by museums and collectors.

- 1977 – the publication “The Poster” (Moscow) releases a photo album, “The Party’s Weapon”, with unique photographs of Lenin’s portraits created by Tikhomirov to embellish the Ministry of Foreign Affairs building, the V. I. Lenin State USSR Library and the Kutuzov Avenue.

- 1980 – composer Oleg Eiges dedicates his piece, “Five Etudes”, to Tikhomirov.

- 1985 – two of A. D. Tikhomirov’s paintings are obtained by the Orel Museum of Fine Arts.

- 27th March 1987 – A. D Tikhomirov’s personal exhibition, “The theatrical images of A. D. Tikhomirov”, takes place at the Regional Dramatic Theatre in the city of Orel.

- November 1987 – a Soviet art exposition opens up in the Orel Museum, where Tikhomirov’s canvases are among the latest acquisitions.

- 1989 – thanks to the assistance of the MARS Gallery, two of A. D. Tikhomirov’s works are demonstrated at the exhibition of Russian art in Rome.

- 1990 – Tikhomirov’s painting, “Theatre Scene”, is successfully showcased in Paris at the Figuration Critique // Paris – Leningrad – Moscou exhibition, where a postcard is published with the image of a fragment of the painting.

- 1993 – the personal exhibition, “Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov”, takes place at the “ANTIP” Gallery in the Central House of Writers in Moscow.

- 30th March 1995 – Tikhomirov dies in Moscow after a prolonged illness.

At present, A. D. Tikhomirov’s works are kept at The Russian Museum (RM), Moscow Museum of Modern Art (MMOMA), in other Russian, as well as Azerbaijani and Italian museums, in private Russian and foreign collections (France, Canada, USA, Australia, and others).

Irina Krupnitskaya

Alexander Tikhomirov’s Biography

(1 January 1916, Baku – 30 March 1995, Moscow)

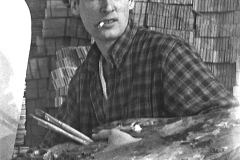

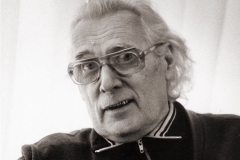

Alexander Tikhomirov is one of the most mysterious and fascinating artists of the last century. He never gave an interview, never tried to explain or comment on his work, wasn’t part of any art committee, and rarely took part in exhibitions. Yet his works – deeply meaningful, challenging compositionally, filled with symbols and hidden meanings – are so eloquent and self-sufficient that it is clear that a creative, unique persona stands behind these works of art.

Alexander Tikhomirov was born on the first day of 1916 in Baku, the olden city of fire, wind and flowery oriental legends.

At the start of the century Baku experienced a powerful economic boom. People from all over the world, of different professions and nationalities, flocked to the city. Dmitri Nikolayevich Tikhomirov, the artist’s father, also came here in search of a job, and soon, thanks to his enterprising and organisational talent, took on an engineering role as a construction foreman in one of Baku’s grand projects: the construction of the Shollar water supply. By 1904, “contractor Tikhomirov” was able to rent a respectable apartment in the city’s Muslim area and bring his wife, Natalia, and their four daughters across from Russia.

The birth of a long awaited son into Tikhomirov’s already large family came at a breaking point in the centuries’-old history of the city. War stood at the very doorstep of Baku, and the once lavish abundance was gradually supplanted by endless mobilisations, hunger and unemployment. While a newborn baby was baptized in Baku’s Alexander Nevsky Orthodox Cathedral by a senior priest and was given the name Alexander, the city raged with a horrific “Womens’ Revolt”, escalating like a storm inside the suffocating, hunger-stricken city. The ruling powers in Baku shifted faster than a kaleidoscope image, and the latently smoldering fire of ethnic hatred, no longer hidden, enveloped the paved streets. That which Alexander lived through within the first five years of his life would easily be enough for a dozen biographies. The child’s tenacious memory retained the horrific episodes of his childhood for the rest of his life: the wail of the crowd, intoxicated by massacre, shattering Turkish neighbourhoods; the hopeless cry of, “Russians! There are only Russians in here!”, which by some miracle turned away the deathly riot from the broken door at Tikhomirov’s house; the cackle of Turkish bashibazouks, ripping earrings out of his mother’s ears and dragging out chests with his sister’s dowry. Till the end of his life, Alexander would remember the Turkish gallows, “decorating” the beautiful parks of Baku, the cold disdain of English officers, and the crowds of Armenians leaving in panic the once welcoming city. The artist Alexander Tikhomirov had yet to live through another childhood horror – in January of 1990, when, watching from the faraway Moscow, he would witness on the screen of his television his native Baku overrun and dominated by a mad crowd.

The city began regaining a relative order only in 1920, with the coming of the Red Army. Russia made unprecedented efforts to giving Azerbaijan the status of a “model Soviet republic”, and the ancient city, having shaken off its bloody haze, soon returned to an ordinary style of living. The best capital city musicians, foreign actors, innovative shows and artistic exhibitions all rushed to Baku, “the city of oriental stories”. Tikhomirov’s sisters practically lived in the Philharmonie, where, every week, there were several concerts of classical music. Meanwhile, his father received the opportunity to add to his collection of gramophone records. There was always music in Tikhomirov’s house, which to the end of his days became for Alexander something natural and necessary, like air. But his most sincere passion, surprising for a child in a family that was distant to art, became drawing. Alexander began to draw very early in his life. He drew everything he saw around him: landscapes, portraits of close relatives… and he drew on anything that he could get his hands on. Not far from Tikhomirov’s home was an artistic advertising studio, behind the low windows of which there was a new, magical world of smells and colours. Alexander spent the majority of his free time either at these magic windows, or in the narrow alleys of the old city, where the esteemed artists often worked. Baku’s wondrous sunsets pulled metropolitan boheme like a magnet. Acknowledged artists of thematic paintings, S. V. Gerasimov, B. N. Yakovlev, F. A. Modorov, A. V. Kuprin, dedicated to Baku their graphic works and paintings. Perhaps it is because of this that Alexander, observing in inspiration their fascinating movements, the mystery, when by the maestro’s wish a completely empty page grew with life, he firmly decided to be an artist.

A tragic event almost brought an end to these aspirations for the future… Despite the newly found cultural luster, the street manners of Baku were brutal, and the artist obtained a serious eye injury in a merciless street fight. Despite all efforts, he was unable to retain sight in that eye. Here, the salvation came thanks to the active support of his father. With his own hands, Tikhomirov’s father cut a window in the wall so that the outside light would fall into the room at the right angle, and created for his son his first easel. In 1931, Alexander, as the only son and helper in the family, began his studies at a technical school and found a job… in Baku’s advertising studio. Soon, circus advertisements and billboards created by Alexander Tikhomirov began appearing in the city to the proud eyes of his family, and especially his sisters and cousins. Despite his busy schedule, Alexander was able to take on private art lessons from an Italian artist, who had surprisingly found a home in the old part of Baku.

Three years later, in 1934, Alexander enrolled into a second year art course in the Baku Art School. The application competition had been huge. The founder of the institute, the self-taught genius by the name of Azim Azimzade, understood like no other the importance of fundamental schooling; the teaching staff there could have brought pride to any State Art academy. The level of preparation at the academy was of such a degree that its graduates were snapped up immediately when applying for big city universities.

At the academy, the extraordinary student found himself in the view of a famous professor, artist Ilya Ryzhenko, a man of great talent and of the most interesting fate, a student of V. Ye. Makovsky. Towards the start of the next academic year, Ryzhenko moved Tikhomirov into his own course. Ryzhenko was a marvelous teacher: his lessons were a real revelation and served as a true school for Tikhomirov. According to Sergei Yesenin, Ryzhenko, himself a friend of the poet, had the rare talent of “creating a story there where others see only dull ordinariness”,[1] and it was he who polished Tikhomirov’s natural talent, instilled in him a genuine artistic culture, and taught him the fundamentals of the classical school.

Tikhomirov, being enraptured and fanatically engaged in his profession, cared not for himself and forgot about everything else, especially those rather meaningless things, as he saw them, such as mathematics and the history of the party… This unique ability to focus on what he believed to be the most important to him played its role in the fate of Tikhomirov. Meanwhile, in 1937, the works of Tikhomirov had already been displayed at the exhibition dedicated to the 750th anniversary of the publication of Shota Rustaveli’s poem, “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin”, which was held at the Azerbaijan State Museum of Art, and after the exhibition was closed, the museum saw it necessary to obtain Alexander’s student works. In 1938, upon finishing his studies at the Art School, Alexander Tikhomirov began working in the Arts Department of Azerbaijan’s Antireligious Museum.

In those years, Tikhomirov actively engrossed himself in a social life. He joined the Union of Azerbaijani Artists, which functioned as an organisational committee for the preparation of an Azerbaijani artists congress. He also took part in the activities of the Young Artists’ Society.

In November 1939, Alexander’s life took a swift turn. Right from a wedding, he abducted another man’s spouse, the woman of his dreams, Nika, who became his wife. To the dismay of his mother, her darling boy, living only for art, became in an instant the pillar of a big family – Nika had a small child, and a helpless mother and a grandmother. Without hesitation, Tikhomirov placed this burden upon his shoulders, as now there was a love incarnate beside him, a woman with the face of an angel and fathomless eyes.

This happiness turned out to be short-lived. Tikhomirov’s newborn daughter died within one year, while the war that started in 1941 destroyed all the established order to its very foundations. Despite all his efforts, Alexander Tikhomirov was refused entry into the army due to his health, so his paintbrush became his weapon. From 1941 on, Tikhomirov worked in the studios of Azerbaijan’s Art Department, where he created portraits of heroes of the Great Patriotic War and paintings on war themes. In order to support his family and simply survive in the conditions of wartime, he also took on private assignments – these earnings were substantial bursaries for the big family. In the summer of 1942 Tikhomirov was forced to leave the city and worked on the outskirts of Baku, in Hudat. There he received the tragic news of his new family passing away from typhoid fever. Alexander hurriedly returned to the city, where he was apprised of another loss: his wife, his beloved Nika, had been pregnant with their second child.

Alexander dived headfirst into work. At the invitation of his teacher, Ilya Ryzhenko, Tikhomirov worked with him on two canvases, “The Overthrow of Hitler’s Forces in the Caucasus” for Baku’s House of the Red Army and Navy. But… in 1944, Tikhomirov decided to leave forever his native Baku, where every corner reminded him of his loss, and he left behind his successful career, his sisters, and the graves of dear ones.

There was no question of where to go – Baku’s creative youth of those years dreamed about Moscow, about its museums and exhibitions, of the opportunity to converse with famous artists. Alexander fervently hoped that in the faraway capital he would be able to enter a sphere of like-minded people, who shared his passion, and who could help in his further development as an artist. The stories recounted by his classmate A. Sahanov, who by that time had finished several courses at the Moscow State Academy Art Institute, was conscripted and received an injury at a battlefield, also played an important role.

So it happened, that in August 1944, despite the firm objections of his teacher Ilya Ryzhenko, Tikhomirov quit the Art Foundation’s Azerbaijani Art Department and, together with A. Sahanov and A. Malkin, moved to Moscow. The capital cherished in dreams received the young Bakuvians coldly and, to put it lightly, looked rather unwell – the first years of war were a trying period for Moscow. Yet despite the prevailing devastation, and perhaps even somewhat thanks to it, the intellectual and artistic life of the capital was experiencing an incredible upsurge. Fate brought Alexander Tikhomirov to the doorstep of the Moscow State Academy Art Institute (from 1948 called the V. Surikov Moscow State Academy Art Institute), during one of the most amazing and romantic periods of the history of this legendary academic institution. At the beginning of 1944, the two parts of the university broken apart due to the war and evacuation were reunited and, in the words of its Rector, Sergey Gerasimov, created a “unified centre, firmly fused by the resoluteness of constantly moving forwards”.[2] The personal and organisational problems – the academy had no building, complete strangers had firmly settled themselves in the old student communal quarters, and in addition to this there were no art supplies and the transport functioned badly – didn’t disrupt the unprecedented flight of creative inspiration.

In 1944, the admission of applicants had sharply decreased. And under otherwise equal conditions, the admission committee unequivocally preferred Muscovites, who did not need living arrangements and vouchers for food in the overcrowded city refectories… And still Tikhomirov passed his entrance exams with excellence and was moved straight into the third course of the graphics faculty. It didn’t matter that, at times, the homeless artists had to stay the night in the university’s auditoriums, where there was not only no firewood but also no furnace. Alexander eventually found a lodging, worked part-time wherever he could … At least now he was surrounded by incredibly gifted people, each and every one of whom was a legend. Alexander Tikhomirov chose his professor himself. And the fact that the legendary “Diamond Jack’ist” and “Cezannist” Alexander Osmerkin was a professor not of the graphics faculty but of the faculty of painting was not of any significance. Having discarded all his other subjects, Tikhomirov, with a dull stubbornness, stayed whole days at a time in Osmerkin’s studio. Fortunately, the organisational dysfunction of the institute allowed for this kind of opportunity. And like a sponge, drop by drop, the artist absorbed in great excitement each word, every movement, the whole generous current of reviving dew pouring into him, that responded to the innermost cravings of the soul… Tikhomirov acquainted himself with artists B. Pinkhasovich, A. Labas, I. Drize, and at one of the evening events met Falk himself. The recognised master noticed the young artist’s “French eye” and invited him to paint a view from the windows of his studio, which was equivalent to being “let into the circle”, acknowledged as an equal, a colleague, a like-minded person!/

In the spring of 1946, new friend Pinkhasovich invited Tikhomirov to one of his wonderful parties, which he loved hosting in his room in a large communal apartment. There, Alexander met a neighbour of Pinkhasovich, Natalia, a student at the Moscow Power Engineering Institute. A youthful beauty, and immediately and unconditionally a believer in the exceptional talent of the young artist, she became Tikhomirov’s love and muse, comforter and inspiration, all in one person – an unexpected gift of fate. After only two weeks, Tikhomirov asked Natasha to marry him and on the 10th April 1946 the happy newlyweds received a certificate of registration of marriage. He was also able to secure a permanent job: starting from May 1946, Tikhomirov became a portrait painter in a studio at the Pictorial Art and Exhibition Department. The artistic life of the first post-war year was filled with ringing enthusiasm: museums repaired after the war were opened, exhibitions of works by Konchalovsky, Kuprin, Ulyanov, Krymov, Falk, Pavel Kuznetsov were being planned in the Moscow Soviet Artists’ Union… Alexander found time for everything. Incessantly and inspirationally, he painted portraits of his young wife.

But Tikhomirov’s fate prepared him a new turn. Like thunder in a clear blue sky, the words of the notorious Zhdanov decrees (1946-1948) sounded, giving a start to a new round of “battling again formalism” in art, and a large-scale cleansing of creative unions. First literature, then theatre and music were sharply criticised for their “spirit of servility before the modern bourgeois culture of the West”. With intensive support from the brainwashed part of the “artistic community” there began a ferocious chase of “aliens”, all those whose aesthetic principles did not conform to the fundamental principles of “social realism”. In 1948, with the “Bolshevik outspokenness”, the “shattering fist” smashed upon the fine arts, which were not considered worthy even of a special decree issued by the Central Committee, or at least of some directive article in “Pravda”. They were fully compensated in August 1947 when the Council of Ministers of the USSR issued a ruling about the renaming of the Russian Academy of Arts into the Academy of Arts of the USSR. The Academy of Arts was basically formed anew and with quite a concrete goal – to wage an uncompromising fight against the “decadent bourgeois culture”. The Museum of New Western Art, the “hotbed of servility”, became the first victim, and was mercilessly liquidated in March 1948. The chef d’oeuvres of Renoir, Degas, Cézanne, Van Gogh were divided between museums and for an extended period of time sent to storage. In May 1948, obediently voicing the wishes of the academic milieu, the “Soviet Art” newspaper let out a torrent of criticism directed towards the Moscow Art Institute, where “the inexperienced, under-qualified professors, people with clearly pronounced formalistic tendencies, such as A. Osmerkin, A. Matveev and others, are educating the youth.”[3] Having carried out a check on the V. Surikov Moscow State Art Institute, the Propaganda Department of the Central Committee of the CPSU found “formalism” both in the art and the actions of the Rector, and so award-bearing RSFSR people’s artist, S. V. Gerasimov, was dismissed. Those students who were admirers of the professor shared his fate. The list of people hiding under “formalism” their “ugly, vicious opinion of reality” was majorly extended and now included the names of literally all, with a small exception, significant artists. Now it was not only Filonov, Tatlin, Udaltsova, Drevin and Malevich, but also Tyshler, Deyneka, Shterenberg, Saryan, Osmerkin, Konchalovsky, Favorsky, Falk – all these artists “found themselves infinitely far from the people; moreover, inimical to it by their way of thinking, as well as by their abstruse, meaningless formalism…”[4]

In September 1948, the orphaned institute opened its doors to its students, but in this renovated “forge of cadres for Soviet art” there was no longer a place for the “groveler” and formalist Tikhomirov. A reason was quickly found: the study fee had not been paid in time (in August, Tikhomirov’s wife had given birth to a daughter), and when the financial question had finally been settled, they remembered about the failed English language exam.

However, the chance to receive a diploma still remained: he was to admit “errors of youth”, “reeducate” himself and prove that he was now a genuine socialist realist. This possibility never registered with Tikhomirov. If his true teachers were oustered…

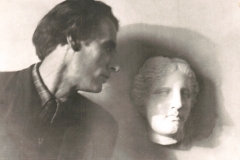

He was driven to wander in search of a job, but… even the light shadow of “modernism” was a black mark. The theatre became his refuge. The unique illusory world, where music never stops and realism intricately entwines with phantasmagoria; a world where inspiration was found by those who were, to Tikhomirov, an unquestioned authority: Azimzade and Falk, Osmerkin and Tyshler… And from autumn 1948, Tikhomirov began working as an artist-painter in the art production studios at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre. It turned out that reality… was somewhat less optimistic, and it began with the sonorous slogan coined by the theatre’s editorial board: “Observe a strict economy of materials. Each saved up rouble is a contribution to the common Soviet cause!” In autumn of 1948, the Music Theatre, in an incredible rush and stress, prepared for the public the opera “The Station Master” by Vladimir Kryukov, despite the fact that there existed no notes from past productions and the opera had to be reinvented from memory. As it later turned out, the enormous tension was an absolutely normal situation and mainly concerned the department of decorations. The endless shifting of outlays and incorrectly filled out orders for materials, brutal squabbles with the supply department for the lack of kraft paper and paints in storage needed for the scenes – all this left little opportunity for personal artistry. Tikhomirov had to paint drawers and chandeliers, weave from discarded materials Solokha’s wattle and, for effect, move the set’s moon across its dark sky background of “air-sea” countless times. But on stage, the Sorochinskaya Market roared and shimmered with colour, clowns wringed their hands, while on Oksana’s carpet there bloomed fantastic green roses…

In May 1949, photographic reproductions of paintings by the most popular western modernists appeared in the magazine “Ogonek” together with damning comments by Alexander Gerasimov, who blamed the artists for having a thirst for world domination and a brutal hatred for man. There were to be no discussions. According to the Art Academy of the USSR President’s strong conviction, the victorious Soviet art had only one more task: to fully uncover the formalists and cosmopolitans, who with servile obsequiousness carried into our reality the ugly phenomena of the decadent western bourgeois art.[5] Already in July 1949, the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre underwent a serious reorganisation, and artist Alexander Tikhomirov, amongst many others, was fired from the studios of the theatre.

A dark cloud of social realism had obscured the whole sky, leaving not the slightest light shining through. The borders, laid out by official ideologues, were equivalent to the death of creativity, while the public searching for independent artistic ways became a risky venture, threatening not only to disrupt a personal well-being, but also freedom. The same threat hovered over the family members – there were more than enough examples of this all around. Tikhomirov couldn’t place his Natasha and his young daughter, named Anelya in memory of his dead child, under this threat; the pain of the irretrievable loss was still too fresh. In the future, till his very death, the artist would protect his girls as much as he could. Whatever fate had in store for him…

It was in 1950 that Tikhomirov began working on the “Holocaust” series, which spanned over thirty long years. The colossal inner tragedy of the artist was in no way reflected in his real, daily life. Tikhomirov grasped onto any opportunity – he worked as an artist at the Central Park of Culture and Rest in Lefortovo, executed orders for the decorative department of Remstroy (Repair and Building Office). He continued to work, complicatedly and pedantically searching out his path, his individual style. Part of the Tikhomirovs’ small room was used as a studio, and soon curious passers-by made a habit of pausing for a while before the big windows of the house on Bryusov lane, where, barely hidden behind the curtain, evolved a fantastic, marvelous world of Tikhomirov’s works.

His friend, colleague and neighbour in the communal apartment, the marvelous genius Boris Pinkhasovich, helped him solve the issue of finding ways to survive. It is simply impossible to overstate the role of artist Pinkhasovich in Alexander’s life. The healthy amount of pragmatism, hedonism and a brilliant ease – all of which this crazy and very talented man possessed within himself – turned out to be truly salvific.

The Department of Decorative Art of the MDAF (Moscow Filial of the Artist Fund) of the USSR, where Pinkhasovich led Tikhomirov practically by the hand, became a refuge for artists who had been ruled out of the community life, branded by all sorts of derogatory epithets, deprived of wages and often hungry in the truest sense of the word. The main, and in fact the only, requirement was a highly professional level. The lack of a completed high art education was not a limiting circumstance; in 1950, Tikhomirov was sent to study at a studio to increase his art qualification at the MDAF USSR Department of Arts and Crafts and, by March 1951, he was hired for a position among the staff.

Those departments existing under Art Foundations had a special autonomy from the Artists’ Union, as first and foremost, they were considered to be expedient organisations. The Art Council, consisting of renowned artists and art historians, accounted for upholding a professional culture in the Department of Decorative Art, and, however opportunistic were the All-Soviet and Moscow Artists’ Union leaders, however servile was their attitude towards authority and the ruling party, they carried out this function perfectly. The quantity of received orders (and the standard of wages) depended for the most part on the efficiency of the artist himself, his connections, the ability to find advantageous side projects, personal charm and negotiations skills…

Alexander Tikhomirov spent only as much time on “official” work as was necessary to support his family. Four-five commissions were found each year without any extra effort – there were not so many portrait artists in the department who were of a similar level, and those with the ability to create a monumental portrait could be counted on the fingers of a hand. At times, earnings from a “big” commission allowed to exist for another year or so. Free time was essential for Tikhomirov, just like air, as his true, real life took place far from the steps of the Department. Painting, and more broadly art, was the air that he breathed. And so what if that which gave meaning to his existence was not needed, not popular and did not “correspond to the political moment”? Beside the artist was his wonderful muse, his wife Natalia Vinogradova, who gave him unconditional support, love and understanding.

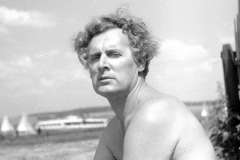

An illusion of spiritual freedom, emerging after Stalin’s death, stirred the creative sphere. The beginning “Thaw” resurrected old hopes, and the artist’s palette began to change dramatically, to blossom with extraordinary combinations. Having no studio in Moscow, for many years Tikhomirov had had one in Troitskoe, a small village on the shore of the Klyazminskoe water reservoir. In those years, this picturesque village congregated those artists continuing the traditions of the 1920s: Labas, Gluskin, Adlivankin, Talberg. After intense, hard work, everyone would gather at Tikhomirov’s rented house, which had been transformed into an object of art by the artist’s fantastic imagination. The whole interior of the country house, including the furniture, was painted into contrasting, ringing colours; it had become an incredible picture. It is likely that never again would so much jubilant colour pour out from Tikhomirov’s canvases onto his audience as did in that “impressionistic” period.

Tikhomirov never ceased to better himself. The artist’s knowledge, as well as his readiness to pay any sum of money for the painfully obtained books and catalogues, impressed his friends. Employees at art museums and salesmen at music stores knew Tikhomirov by face; he was the permanent listener at the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall and Moscow Conservatory. His passionate love and detailed understanding of music brought the artist closer to the greatest musicians, many of whom become his friends and admirers of his talent. In 1968, one of Tikhomirov’s paintings, “Paganini”, was acquired by a well-known violin player, E. G. Gilels, the wife of the genius violinist L. B. Kogan, and, to the joy of the artist, it embellished the living room of the unsurpassed musician.

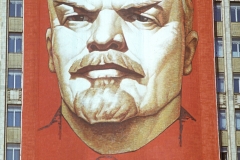

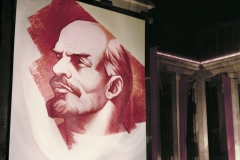

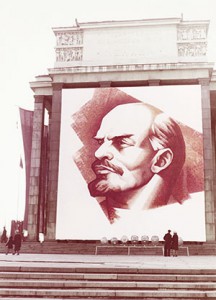

In 1973, under the commission from the Department, Tikhomirov, together with a colleague and friend, I. M. Ilyin, painted a portrait of Lenin which was forty-two by twenty-two metres in size and was placed on the facade of the USSR’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs building. The artists worked on the portrait at the Central Dynamo Stadium, having spread out an enormous canvas over the football pitch. The portrait evoked great delight in an honorary Moscow guest – the renowned Italian painter, Renato Guttuso, who was passing by the Smolenskaya Square in a car with the Party Committee’s First Secretary, Grishin. The creator of this masterpiece was promptly summoned to the Moscow CPSU City Committee. The admiration of the honored guest had also some practical consequences: by the active cooperation of I. Ilyin Alexander Tikhomirov at last obtained his personal studio. In 1975, this work, performed on special strips, was given a gold medal by the VDNKh. The foreign press, poor for praise, immediately labelled the Department’s leading artist in the creation of Lenin’s image as a “billboard propaganda classic”.

Questions of career, titles, or regalia, that enhance life in numerous ways, did not interest Tikhomirov. In the artist’s opinion, all this had no link to art. The unexpected studio became his refuge, his temple, where an altar of true art was erected.

Into this “Holy of the Holiest”, his studio, the artist allowed only the dedicated, who he determined by characteristics known only to him. He very reluctantly showed his works to strangers. But those who were able to step over the coveted threshold, found themselves for a long period of time under an impression of striking contrast with the surrounding reality and fantastical temperament of what was seen. In 1975, a well-known art historian V. Moskvinov acquainted Alexander Tikhomirov with V.A. Matveev, at that time a docent, now a professor at Bauman Moscow State Technical University, and at that time, a new, just-starting-out collector. With a subtle prompt from his side, a significant part of the MSTU professorial staff joined the ranks of admirers of the artist’s creations. Tikhomirov’s paintings, as Matveev said, were “a model of balance in some kind of oddity, an engineered balance to be exact. And at the same time they always carry some sort of a creative meaning. This is what was always incomprehensible.” The artist’s attempt to acquire a new outlook, a new idea, to step into the hitherto unknown, the wish to deeply investigate into the essence of occurrences, found a profound understanding in the techno-scientific elite. Moreover, even ten years after the death of Tikhomirov, when the increased appetites of the proprietors made it practically impossible to save his studio, it was none other than the Bauman MSTU that for two whole years gave sanctuary to the homeless canvases, allocating a specially equipped room for their safe storage.

In 1976, upon reaching the age of retirement, Tikhomirov left the Department and almost literally moved to live in his studio, where he, without distractions, could now develop all his creative thoughts. Yet the Department called upon the maestro more than once – in 1976-77, in 1980-83 – though these were one-off orders, incapable of changing the artist’s established daily rhythm. According to the reminiscences of Tikhomirov’s daughter, Anna, having “put on Stravinsky’s ‘Petrushka’ at almost full volume, the artist fell into a trance and, liberated, transferred himself into a state of free flight. Paintbrush in hand, he performed a frenetic shamanic dance before his canvas. And so the canvas transformed into a mirror, reflecting the most deep of experiences.” Scriabin, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Beethoven, Carl Orff sounded in the artist’s studio, elating, inspiring and taking him away, as he worked. Especially Stravinsky… The works of Tikhomirov were described by his friends – composers and pianists – as “music embodiments”, while composer O. K. Eiges dedicated one of the “Five Plastic Etudes” to the artist.

In 1985, The Orel City Museum acquired two of Tikhomirov’s works, painted in 1970, and on the 27th March 1987, Alexander Dmitrievich’s first ever personal exhibition “The theatrical images of A. D. Tikhomirov” took place in Orel State Drama Theatre. This exhibition provoked a genuine interest from the public and… slightly startled the press. For the 70th anniversary of the Soviet State, an exposition of Soviet art was held at The Orel Museum, where, amongst the latest acquisitions, were canvases by Tikhomirov. A literary and art consultant at the CPSU Central Committee, the former Orel citizen N. M. Chernov, visited the exhibition. His reaction formed one short sentence: “I wish to never see this again”, and so the museum was forced to decline buying Tikhomirov’s paintings after the exhibition in the Orel theatre.

And still, times visibly changed, and already in 1989, thanks to the assistance of the “Mars” gallery, two of A. D. Tikhomirov’s works were demonstrated at the exhibition of Russian art in Rome. And in 1990, Tikhomirov’s work called “Theatre Scene” was met with success in Paris at the exhibition “Figuration critique: Paris-Leningrad-Moscou” at the Grand Palais Gallery, where postcards were produced with the image of a fragment of the painting.

The artist was literally bumped by the ceaseless flow of invitations from Italy, England, France… Tikhomirov didn’t seriously consider them. From his point of view, all that he needed he already had at home, and a separation of an artist from his roots was, in his opinion, equivalent to the death of creativity.

The seventy-four year-old artist spent every day in his studio, usually eight to ten hours. He allowed himself no concessions even when his health started to let him down, because for Tikhomirov art was his very life.

The last personal art exhibition of Tikhomirov that was held during his life took place in 1993 at the “ANTIP” gallery in the Central House of Litterateurs.

Tikhomirov passed away on the 30th March 1995 in Moscow after a continuous sickness, leaving his final work unfinished on the canvas –Arap [dark-skinned man], adorned with a black bow-knot and almost bursting out of his flesh, not fitting even into the canvas’s boundaries, condescendingly observes a tiny Petrushka, literally crucified between his monstrous fingers.

The physical and spiritual time in which the artist lived and created was that of a crushing power of the crowd… But if to follow closely the libretto of Stravinsky’s ballet, so loved by the artist, the performance does not end here. And so the life of Tikhomirov’s artistic heritage has only just begun.

[1] N.K. Verzhbitsky. Encounters with Yesenin//S.A. Yesenin in the Reminiscences of His Contemporaries. Moscow, 1986, vol. 2, p. 156.

[2] I. E. Grabar. A Speech during the Approbation of the Diploma Works in November 1942.

[3] “The Soviet Art”, May 29, 1948.

[4] G. Nedoshivin. Essays on the Theory of Art. Moscow, 1953.

[5] “For Soviet Patriotism in Art”, “Pravda”, February 10, 1949.

LIFE IN MOSCOW

In January 1944 Alexander Dmitrievich left Baku. He was planning to enter the Moscow Surikov Art Institute. He has been admitted in 1945, straight into the 3rd year of studies, into the workshop of A. Osmyorkin. However, his studies didn’t last long: already during the 4th year of studies he has been expelled for ‘formalistic’ trends in his art. Over some time he worked as a freelance artist, and in 1949 he started working at the Applied and Decorative Arts Concern.

Bryusov lane

Moscow period of the artist’s life is associated with the house in Bryusov lane, where he lived together with his family for almost 20 years.

Unfortunately, this beautiful three-storey house with bay windows, no longer exists these days. Only few buildings of those times remained in Bryusovsky, nowadays Bryusov lane, and a beautiful Church of the Resurrection, with fresco paintings, so much admired by the artist.

Communal flat with a huge kitchen and a back entrance in a three-storey brick house was inhabited by six families. All inhabitants lived in piece and lead an interesting life. Among the neighbors of Tikhomirovs was Petrovs couple – Vera Semyonovna and Arkady Nikolaevich.

Memories of Natalya Anatolyevna Vinogradova:

‘Vera Semyonovna was holding the concerns of classical music at home, with involvement of the famous musicians. Sometimessuchconcertshavealso beenattendedbyinterestingartists. It is during one of such concerts Alexander Tikhomirov got acquainted with Robert Rafailovich Fahlk. Later on their acquaintance grew into a friendship. Fahlkinvitedthe young artist into his workshop, where Alexander Dmitrievich introduced him to his works, including the still-lives and landscapes done in impressionistic manner. The works of Tikhomirov left a very good impression on Fahlk. Once, speaking with Tikhomirov, he noted that Alexander Dmitrievich has ‘a French eye’ in art and invited him to make a sketch of the view from the window of his workshop. Alexander Dmitrievich said that similarity of their views on art issues allowed them to find lots of areas of common interest. Later on, Tikhomirov has become a frequent guest at Fahlk’s workshop.

‘Vera Semyonovna was holding the concerns of classical music at home, with involvement of the famous musicians. Sometimessuchconcertshavealso beenattendedbyinterestingartists. It is during one of such concerts Alexander Tikhomirov got acquainted with Robert Rafailovich Fahlk. Later on their acquaintance grew into a friendship. Fahlkinvitedthe young artist into his workshop, where Alexander Dmitrievich introduced him to his works, including the still-lives and landscapes done in impressionistic manner. The works of Tikhomirov left a very good impression on Fahlk. Once, speaking with Tikhomirov, he noted that Alexander Dmitrievich has ‘a French eye’ in art and invited him to make a sketch of the view from the window of his workshop. Alexander Dmitrievich said that similarity of their views on art issues allowed them to find lots of areas of common interest. Later on, Tikhomirov has become a frequent guest at Fahlk’s workshop.

Alexander Dmitrievich also established warm friendly relations with the artist Evgeny Andreevich Dodonov. Thisgreat and deep artist has endured terrible life trials, having spent several years at Stalin’s concentration camps; however, he managed to retain his love to art and ability to continue his work. Tikhomirov has also been friends with the talented artist Efim Davidovich Simkin’.

Tikhomirov maintained friendly relations with many artists, including A. Labas, B. Talberg, A. Peredny, I. Ilyin, I. Drize, and B. Otarov. He also became friends with his neighbor – the artist B. Pinkhasovich.

Among its friends and acquaintances there were musicians and composers. Having been taken by symphonic music in his younger years, Alexander Dmitrievich carried passionate admiration for it throughout his entire life. In Baku, he was collecting phonograph records, and, having locked himself in the room listened for operas and symphonies for hours. When he lived in Moscow, he was constantly re-filling his collection and, just like the book shops, he never missed a musical store during his walks, which the artist admired so much. He listened to compositions of Scriabin and Stravinsky, Beethoven and Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Debussy and Karl Orff for hours and many times. He liked going to the concerts, often attended the Conservatory, was a great expert and admirer of classical music, thorough listener and, according to his friends, knew it better than some musicians. He always worked with the music on and an old radio-gramophone ‘Regonda’ has always been a must object in his room in the communal flat, in his country cabin during the summer and later on in his workshop.

Another hobby of the artist was cinema. In Baku Tikhomirov collected the cards with photos of the cinema actors. In Moscow he continued being fond of cinema. His wife Natalia worked at the Research-Scientific Cinema and Photo Institute, which gave him an opportunity to watch fresh cinema releases from abroad. Later on Alexander Dmitrievich will highly appreciate movies by F. Fellini, which will attract him with deep psychological collisions and theatricality of the characters. Impressions from these movies will be reflected in the artist’s paintings and graphics.

Work at the Monumental-Decorative Art Concern

In 1949-1976 Alexander Dmitrievich worked at the Moscow Monumental-Decorative Art Concern (KMDI). Though, the artist continued taking official orders long time after his retirement in 1976.

In 1949-1976 Alexander Dmitrievich worked at the Moscow Monumental-Decorative Art Concern (KMDI). Though, the artist continued taking official orders long time after his retirement in 1976.

While working at KMDI, Tikhomirov painted portraits of V.I. Lenin and the members of Politbureau. These portraits were used to decorate buildings and streets of the capital during the national holidays. And in Soviet art of 1950-70-s Tikhomirov was known as the author of Leniniana, who painted the leader’s world largest poartrait (42×22 m), placed on the frontage of the building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during the official celebrations.

Renato Guttuso, who visited Moscow in the middle of 1970-s and saw Lenin’s portrait on the building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, admired mastery of the artist. Later on this portrait was performed in special ribbons and in 1975, upon recommendation of the Culture Department of the KPSS City Committee, awarded with the golden medal at the Visual Propaganda Exhibition held at the Exhibition of Economic Achievements.

In 1977, “Plakat” publishing house (Moscow) released photo album “The party’s front-line weapon”, which became a rarity nowadays. This book devoted to promotional posters contains unique photos of works of the Soviet artists (1960-70-s) – posters, panel paintings and stands, – starting from the portraits of Marxism-Leninism leaders and up to dynamically lit installations used for illumination of streets of Moscow.

In 1977, “Plakat” publishing house (Moscow) released photo album “The party’s front-line weapon”, which became a rarity nowadays. This book devoted to promotional posters contains unique photos of works of the Soviet artists (1960-70-s) – posters, panel paintings and stands, – starting from the portraits of Marxism-Leninism leaders and up to dynamically lit installations used for illumination of streets of Moscow.

Among others, the books presents photos of Lenin’s portraits, created by Tikhomirov for decoration of the building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, USSR State Library named after V.I. Lenin and Kutuzovsky avenue.

Official orders took much of his time, however, allowed Alexander Dmitrievich retaining financial independence which he so much needed for his own art and embodiment of his own conceptions.

Over these decades of his creative development he passed through the stages of impressionistic, post-impressionistic and fauvist art and worked out his own bright and unique style. He experimented a lot with color, texture of the canvas and composition, found unusual plastic solutions and demonstrated masterful possession of various painting techniques. In his art Tikhomitov appealed to a person’s inner world, depths of subconscious, eternal questions of being and search for one’s true “self”. His works are characterized by deep psychological content of his characters and multiplicity of philosophic subtexts. No wonder that it was impossible to exhibit works on Biblical, oriental, theatric and circus themes during the Soviet times and the first exhibition of Tikhomirov’s works took place only in 1987.

TROITSKOYE

Alexander Dmitrievich devoted summer months to his own art. Not having a studio of his own, he acquired one near Moscow, in Troitskoye village, where during the first half of 60s Tikhomirov’s family was renting a little house on the land plot along Klyazminskoye water reservoir.

Alexander Dmitrievich devoted summer months to his own art. Not having a studio of his own, he acquired one near Moscow, in Troitskoye village, where during the first half of 60s Tikhomirov’s family was renting a little house on the land plot along Klyazminskoye water reservoir.

Troitskoye of that time was a “smaller Abramtsevo” for the artists who followed the traditions of the 20s. Just like Tikhomirov, such artists as S.Y. Adlivankin, A.A. Labas, I.M. Glouskin, B.A. Talberg came here to rent rooms and houses from local residents. Tikhomirov remained friends with them during the following years. The artists worked hard during the day and during the evening they gathered at Tikhomirovs’ to share their impressions and discuss new works.

From the memories of Anna Tikhomirova, daughter of the artist: «all of them were attracted by his unusual works and fantastically transformed rooms of the country house. The artist’s powerful temper captured the space. Paintings seemed to be ‘spilling out’ of frames, transforming interior of the house and flowing into the street. All furniture in the country house was painted into contrast, ringing colors, the whole room turned into a picture. Bright palettes of various shapes settled on the floor and the walls. Resonant, unusually shaped palettes were all over the floor and the walls, the shelves were filled with marvelous still lives, where usual objects lost their ordinary designation, striking our eye-sight with a new and unexpected perception. The only thing that was never colored and remained itself was the old radio and record player – a sacred thing to the painter, who would always work to classic music. The garden was decorated with whimsically painted beach chairs, even the kayak, painted in Indian style, striking imagination of the local boatmen”.

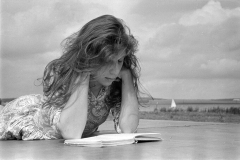

Tikhomirovs spent in Troitskoye three summers in a row. Alexander Dmitrievich worked a lot, devoting every day to his art. During the hours of rest they organized home performances, played badminton and went out walking in the surroundings. With its bright sunset colors, cavalcades of yachts and sailboats sliding along the river Troitskoys reminded the artist of Baku, inspiring him for creation of new works. It was here where Tikhomirov painted multiple landscape and a series of fauvist works on commedia dell’arte theme named “Petroushka and Ballerina”. The latter were striking with richness of colors and unusual rhythms – pastous strokes seemed to be spinning in festive dance. Inspired by Stravinsky’s ballet “Petroushka”, these paintings were devoted to the artist’s muse – his wife Natalya Anatolyevna. The theme of great, dedicated love will remain one of the main themes in Tikhomirov’s art. The artist used to say: ““Petroushka and Ballerina” is a theme which has always been capturing me”.

FAMILY

Natalya Anatolyevna Vinogradova (1923—2008), wife of Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov. Combustion engineer.

Natalya Anatolyevna Vinogradova (1923—2008), wife of Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov. Combustion engineer.

Born in Egorievsk in the family of the White Guard officer Anatoly Vinogradov and Alexandra Konyushkova. In 1942-1947 studied at Moscow Energy Institute. Married Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov in 1946.

From 1949 worked as senior engineer at All-Union of the Order of the Red Banner of Labor Heat Engineering Scientific-Research Institute named after F.E. Dzerzhinsky, in 1960-1970-s – at All-Union Scientific-Research Cinema and Photo Institute (NIKFI). Was among the authors of a number of inventions in the field of chemical-photographic processing of a motion-picture film strip and its transfer inside photographic developing machine. Awarded with the silver and bronze medals of the Exhibition of Economic Achievements for achievement in the field of building the national economy of the USSR.

Was fond of literature, philosophy, arts and cinema. Played the piano, often organized home concerts. Spoke German, French and English languages, did literature translations.

The text is comprised using materials from the archive of Tikhomirovs’ family.

Anna Alexandrovna Tikhomirova (1948—2006), daughter of Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov. Monumental artist.

Anna Alexandrovna Tikhomirova (1948—2006), daughter of Alexander Dmitrievich Tikhomirov. Monumental artist.

Born in Moscow. 1967-1972 studied at Moscow Publish Institute. Worked on decoration of a private villa and the school hall in London. Made sketches of costumes and decorations for “The Greedy” opera by V. Pashkevich in B. Pokrovsky theatre. After perestroika was doing freelance works (Moscow Beauty Institute – decorative panel, painting of the school hall in Degtyarny lane, etc.).

Along with monumental orders worked on the easel paintings using oil and tempera art techniques in a style which could be referred to as fantastic expressionism. Main cycles of works: “Petersburg phantasmagories”, “Dreams”, “Marriage paradigm”.

Thoroughly studied philosophy and psychology – works of Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and their successors. Was an expert in horse-riding, played the piano, was fond of pantomime, studied gypsy, oriental and Spanish dances, tango. Spoke English and Italian languages.

The text is comprised using materials from the article by V.A. Matveev, the book “Bequeathed to Oryol” (Oryol, publishing house of Oryol Art Gallery, 2005) and Tikhomirov’s family archive.

Ekaterina Gogoleva